4.32 Front and Back Counters

Chapter 4: the Self-Controlled

Setting out from Accounting, K’s uncle tasked him with making his way through the dealership to Wholegoods and then prove to Navistar and everyone else that he could be a leader in truck and bus sales. This being the case, K’s stint in the Parts department would seem to be little more than a stepping stone. When we pay closer attention to a few details, however, this impression quickly dissolves.

Recall, for example, the DEALCOR manual that K found in the computer room during his first week in the dealership. That manual contained numbered sections. The order of those sections now takes on a certain significance: “1 New/Used Trucks,” “2 Parts,” “3 Maintenance…” This is not the first time that we have encountered this order—for instance, this is the same order we found in the dealership’s marketing brochure (cf. §1.21 The Brochure). This order needs to be accounted for if only because it deviates from the order and series of assignments that make up K’s learning process—namely: Accounting, Parts, Service, and Wholegoods.

In fact, it is from the point of view of Navistar’s sales and profitability that Parts comes after Wholegoods and before Service: International dealership parts operations are a major source of revenue for the OEM. This fact also manifests itself in Navistar’s corporate structure with its three divisions: “Vehicles,” “Engines” and “Services”. The word “Services” must not be confused with “Service” when that word names the dealership’s “Service department”. Rather Navistar’s “Services” division consists of three brands or companies: “Navistar Financial,” “Navistar Electronics” and “Navistar Parts”. The dealership’s Parts department is a local distributor for Navistar Parts.

If the dealership’s Service department comes after Parts in its own marketing materials and in the Navistar International-supplied materials such as the DEALCOR manual, it is because, from the point of view of the OEM, the dealership’s Service operations function as a “necessary evil”: unlike Wholegoods and Parts, the dealership’s Service operations constitute a major expense for Navistar and other OEMs in the form of “warranty work”.

This is precisely the opposite situation for dealers themselves: both Parts and Service represent the “bread and butter” of the dealership. Together, those two profit-centers are expected to “absorb” one hundred percent of the dealership’s total cost structure. This is expressed in what is known as an “absorption rate”.

With these considerations in mind, we can return to our focus on the built space of the Parts department. As we began to explain in the previous section, Bruce made the decision to put an office cubicle directly in his line of sight to the front counter. This made sense because Bruce does not discipline his Parts people by keeping a constant eye on them. Such an observation is consistent with Bruce’s “management philosophy”: “I manage by doing and by walking around.”

Bruce does not walk around in order to keep an eye on his people, although he is certainly able to do so as a result. Rather, in walking around he is doing the same thing that K’s uncle does on his routine walk around the dealership: he walks around in order to be seen, to let others in the dealership know that he is on the job and that he is “with them” (cf. §1.22 The Walk Around).

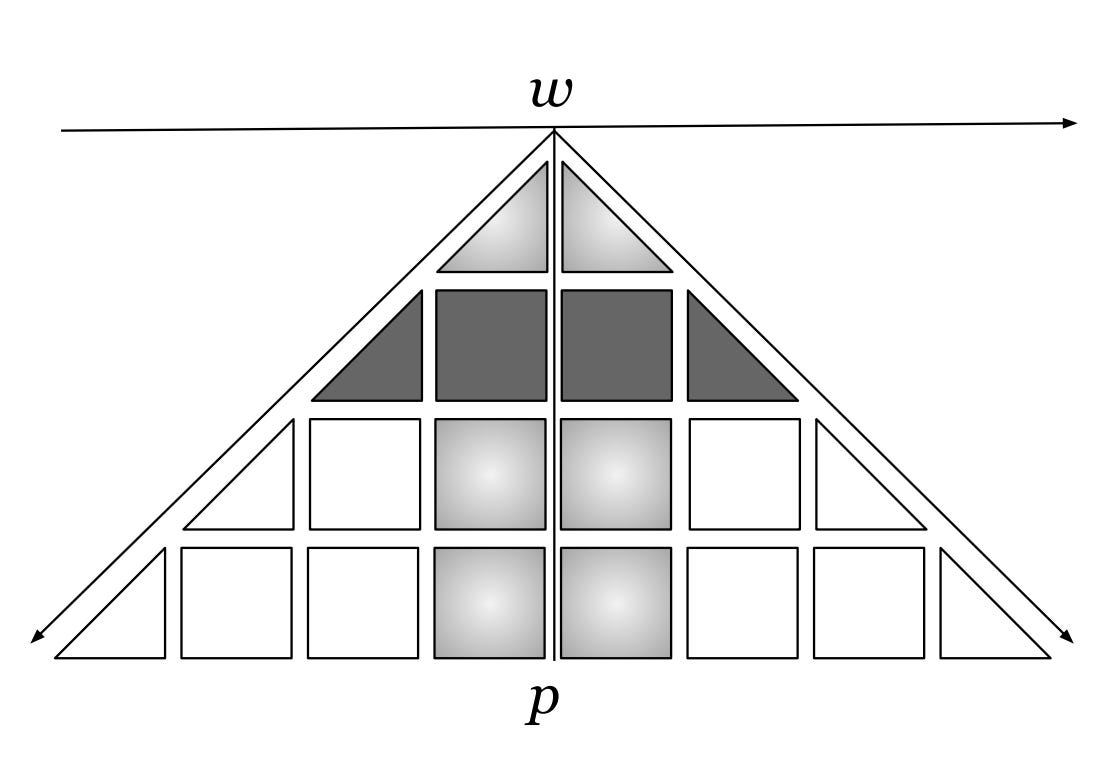

It is at the back parts counter (d) that Service meets Parts and it often appears like two worlds colliding. Except for after hours shifts (swing, graveyard and Sunday), the back parts counter is reserved for selling parts to the dealership’s Service department. The Parts department’s imperative to minimize its cost structure interferes with the Service department’s efforts to achieve maximum productivity and a minimum of “come backs” in the performance of “billable hours”.

The fact that the counter that serves the Service department is referred to as the “back” parts counter casts some light on the situation: like most “backs” relative to “fronts,” it is relatively undervalued and treated as such. It is not only called “back” but, as we described above, Bruce literally has his own back turned away from it when seated at this desk. Compared to the front counter and showroom floor, the back counter is a captive market.

This same back-front axis informs other built spaces in the dealership: the front and back lots of the dealership taken as a whole—the Wholegoods department and its new stock vehicles are kept on the “front lot,” while customer vehicles in for repair and the Service department itself use the “back lot”.; there is the less obvious case of the Accounting “offices up front,” those of the Controller, Uncle John and AJ, and then there is the “back Accounting office”; in the Service department itself, the front and back scheme appears as follows: preparation and delivery of sold-in-process vehicles is carried out at the front of the shop floor while the body shop was housed in the far back—that is, until it was moved altogether to Diamond Truck Center.

In every case, the front is positively coded and the back negatively. The fact remains, however, that nowhere in the dealership is the front/back scheme more apparent and more inscribed in the routine practices and understandings than in the Parts department.

A note from K’s journal headed “Shop Floor as Captive Parts Market” indicates that he was already aware of this to some degree:

In my estimation, the shop floor is the single most under-developed market for our Parts department. As I noted in my summary report on the Parts department, “a Parts person on the shop floor learns more, more quickly and develops a level of camaraderie with members of the Service department not possible when situated at the Back Parts counter”. Our Parts and Service Departments need to come to the table to formulate such a plan that promises to increase Back Counter Parts Sales, Service Center Sales and Shop Productivity.

When we followed Uncle John on one of his walk arounds, we imagined him asking Bruce and Cal to “come to the table” for precisely this reason. Despite K’s recommendation and the Service department’s pleas, nothing ever really changed at the back parts counter or on the shop floor. In the next chapter, we will revisit this issue with the aim of further specifying the relations between Parts and Service.

Observations such as these eventually led K to recall the small sun bleached sign perched atop the whiteboard in the conference room, “ATTITUDE IS EVERYTHING!”

What is the story behind that sign? When K asked Uncle John he replied curtly, “Since the beginning, I reinforced whenever I could that ‘positive attitude’ was necessary for success. And it is!”

Thinking there might be more to the story than that, K put the same question to Bruce and was not surprised when he replied:

“At the time those words first appeared on the white board (authored by self), buzz words and phrases were flying about the dealership as a way to zero in or focus on issues at hand. JDM led the charge with…a few phrases to give lead to the written phrase. At the time the words appeared [on the whiteboard], not all was going great and meetings could at times be a public execution of one’s person. Me being a man of action and direct words, I placed this phrase in front of all as a reminder of what our joint mission was. Regardless of the business situation and the outcome truly ‘Attitude is everything’. These words moved the theme of our meetings in the upcoming weeks. Never was a comment made as to the author, the meaning or the intent. The message must have meant something as those words were written in erasable marker and no one erased them for several weeks. The written word is a powerful reminder.”

K’s uncle and Bruce both failed to acknowledge or perhaps simply forgot that the expression “Attitude is everything!” appears repeatedly in the training materials that had been used in the dealership for many years.

Paul J. Meyer, who authored those materials, defines attitude as a “habit of thought”. During his second year at the dealership, K would go on to complete several such courses himself and, in doing so, came to admire this formulation first as a compelling call to action—recognize negative attitudes and replace them with positive attitudes—and eventually as a powerful propaedeutic—with positive habits of thought leading him to a remarkable Image of Thought that challenges our “our inveterate habit of thinking difference on the basis of the categories of representation.”1

Gilles Deleuze, Difference & Repetition, p.119.