1.32 Mapping the Field

Chapter 1: The Soul of Business

The field of participation is the “plane of organization and development” and is necessarily determined by a certain “transcendence” that distinguishes it from “the plane of immanence or consistency”.1

From a cognitive ethnographic perspective, the former appears as a series of overlapping communities of practice and corresponding control mechanisms and the latter as a “universal encyclopedia”2 or the “immense thy of a pig”.3

From an ethological perspective, the former appears as variously connected “Umwelt” held by disparate animals or beings, unequal representatives of labor power and agents of capital (“society of human beings”) and the latter as a scientific “Welt” populated by diverse equals (“community of rational beings”).4

From a topological perspective, the former functions as a “global relative” and the latter as a “local absolute” 5 ; or, in technical terms used by the mathematician in tune with the philosopher, the former functions as “a ‘worldly’ pole: a multiplicity V,” and the latter as “a ‘transcendental’ pole: a ‘total space’ E.”6

In terms of method, we approach the field of participation or plane of organization and development as a “false problem,” recognizing that today “there are those for whom the whole of differentiated social existence is tied to the false problems which enable them to live, and others for whom social existence is entirely contained within the false problems and from which they suffer.”7

Framed in these terms, the philosopher is unequivocal in his assessment of our challenge: “Without the ground it is impossible to distinguish true from false problems.”8 And what is particularly challenging or pernicious about the contemporary “social problem” is that it effectively envelops the ground: “capitalism’s immanent axiomatic”.9 The ground is the problem.

As such, it will only be possible to distinguish the true from the false problem by demonstrating how the ground itself participates in “a world already precipitated into universal ungrounding.”10

By carefully following K through his experience learning the family business, we can demonstrate how this precipitation unfolds “in virtually geometric progression”.11

Our demonstration begins by mapping “the objective field of the false problem”.12 Such a mapping corresponds to “the second, transformational” component of what the philosopher calls “pragmatics”.13 Our demonstration continues in the second volume of our larger publishing program, which moves on to the third “diagrammatic component” of pragmatics.

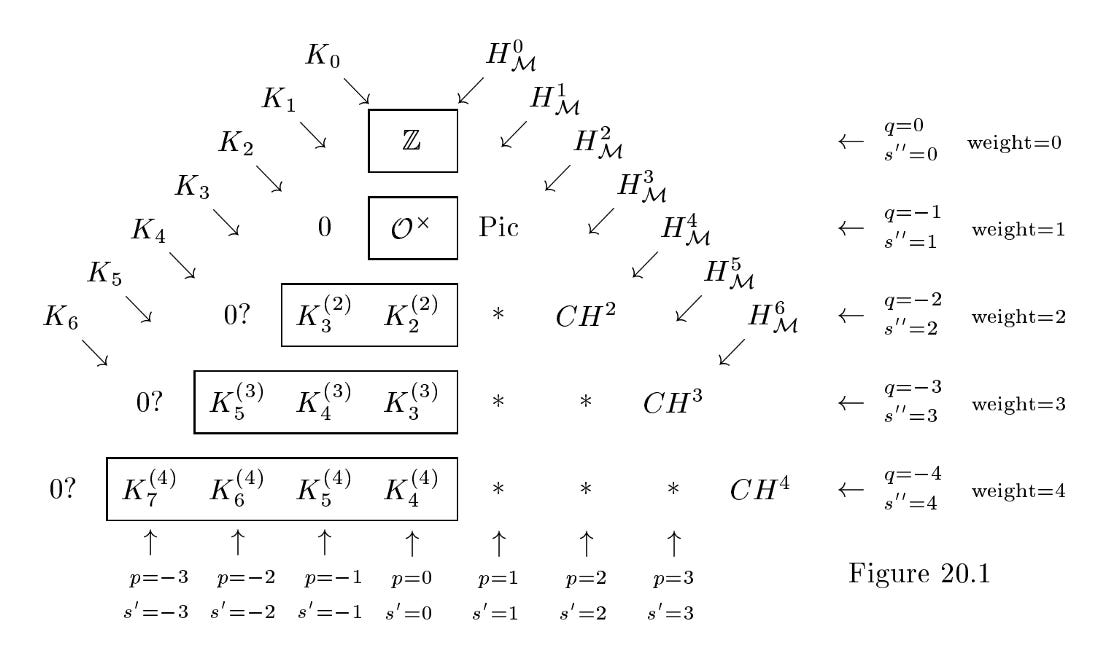

And going from one to the other will require us to take the other “road to mathematical comprehension,” as our cartographic and topological intuition gives way to the rigorous proofs of “abstract algebra.”14 In doing so, the K-function that forms an “image of thought” (that which can be seen, but is only an effect) gives way to a dimension that requires a new notation and constitutes a “thought without image” (that which exists, but cannot be seen).15

Such are “the two odd, dissymmetrical and dissimilar ‘halves,’ the two halves of the Symbol” or what we now see and understand as the Absolute.16

Not surprisingly, making the move from one to the other and grasping the two together require a Spinozist inspiration. In his Theological-Political Treatise, the “Christ of philosophers” proclaims:

“There’s no point in piling up biblical evidence for this. Anyone can see that knowledge of God wasn’t evenly distributed throughout the faithful. And anyone can see that no-one can be knowledgeable on command, any more than he can live on command. It’s possible for all people — men, women and children — to be equally obedient, but not for all people to be equally knowledgeable. Possible objection: ‘Indeed it isn’t necessary to understand God’s attributes, but it’s necessary to believe in them, this being a simple belief not backed up by any demonstration.’ Rubbish! Invisible things are the objects only of the mind, not of the senses; so the only ‘eyes’ they can be seen by are, precisely, demonstrations. So someone who doesn’t have demonstrations doesn’t see anything at all in these matters. If they repeat something they have heard about such things, that doesn’t come from their minds or reveal anything about their minds, any more than do the words of a parrot or an automaton, which speaks without any mind or meaning.”

Describing thought as “fast and slow” is a necessity, but any theory of cognition that does not extend to include and account for the mind’s “eyes” and thought as “creation,” for the “absolute” speeds of thought no less than the “relative” speed of “habit” and slowness of “active memory,” is at best a partial and incomplete theory of cognition.17 From our vantage point, it side steps and ignores what is most “Interesting, Remarkable or Important” about thought.18

Like other cognitive ethnographers, we find “that the effects of peripheral participation on knowledge-in-practice are not properly understood; and that studies of apprenticeship have presumed too literal a couple of work processes and learning processes.”19

How do those basic processes hold together in practice? How are their relations articulated? “In order to distinguish this or that individual,” the processes and principles involved “do not allow themselves to be guided by simple contrasts or by crude quantitative inequalities proceeding from partitions and manipulations of already accomplished individuals which reduce measurement to a balance sheet of which one hopes it will be able to gather them into a presentable totality.”20

Only the field of participation can adequately account for the complex relations between learning and work, for individuation and already accomplished individuals and for the precise manner in which the two are held together or connected as a function of commercial practice. Moreover, only that field can account for how learning and work are complexly related to the larger or total field of play—“the line of the outside”.21

In what follows, we begin to lay out the complex relations of our field or plane by first taking up “working relations” before turning to the “learning curriculum”. This order merely facilitates our presentation, and should not be interpreted as an indication of relative importance. Working relations and learning curriculum are both integral dimensions of the target situation, combining to form a “region of copresence”.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p.281.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, What is Philosophy?, p.12.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus, p.38.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p.62.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p.382.

Gilles Châtelet, “On a Little Phrase of Riemann’s…” (www.urbanomic.com)

Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p.208.

Gilles Deleuze, What is Grounding?, p.176.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus, p.250.

Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p.202.

Niklas Luhmann, Organization & Decision, p.307.

Ibid, p.208.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p.145.

Hermann Weyl, “Topology and Abstract Algebra as Two Roads of Mathematical Comprehension,” in Levels of Infinity: Selected Writings on Mathematics and Philosophy, pp.33–48.

Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p.132.

Ibid, p.279.

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, What is Philosophy?, p.82.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situation Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, p.95.

Gilles Châtelet, Figuring Space, p.66.

Gilles Deleuze, Foucault, p.120