Despite everything, International managed to avoid bankruptcy and to do so without any government intervention. Moreover, as some observers are careful to point out, even while the company’s own survival was still in doubt it went out of its way to assist former employees and their families in making the most of a bad situation. For example, the company set up “outplacement centers” at each location and staffed them with employees who had themselves lost their jobs:

“In addition to monetary separation packages—including severance pay based on service and tenure, and one year’s continuation of health and life insurance with the option to continue them beyond that period at the individual’s expense—the company offered a variety of other outplacement services. Job search assistance workshops were set up with spouses invited. Training was provided for resume preparation, cover letters, long distance telephone service, reference materials, job clubs, various forms of counseling (family, financial, legal), testing and assessment, job development (placement), company tuition refunds, retaining classes, and relocation assistance.”1

While the company took steps to help former employees and their families pick up the pieces of their shattered lives, it was also in the process of what some observers described as “restructuring for self-renewal”.

This meant “positioning the company for a new future” by “returning to the businesses it knew best,” which no longer meant “agricultural and construction equipment” but rather “medium and heavy-duty trucks and engines.”2

The most conspicuous element of this new future concerned the company’s “corporate image”. Having sold the name “International Harvester” to Tenneco in November, 1984, the company went through an intensive process and eventually decided to rename itself “Navistar International Corporation”.3

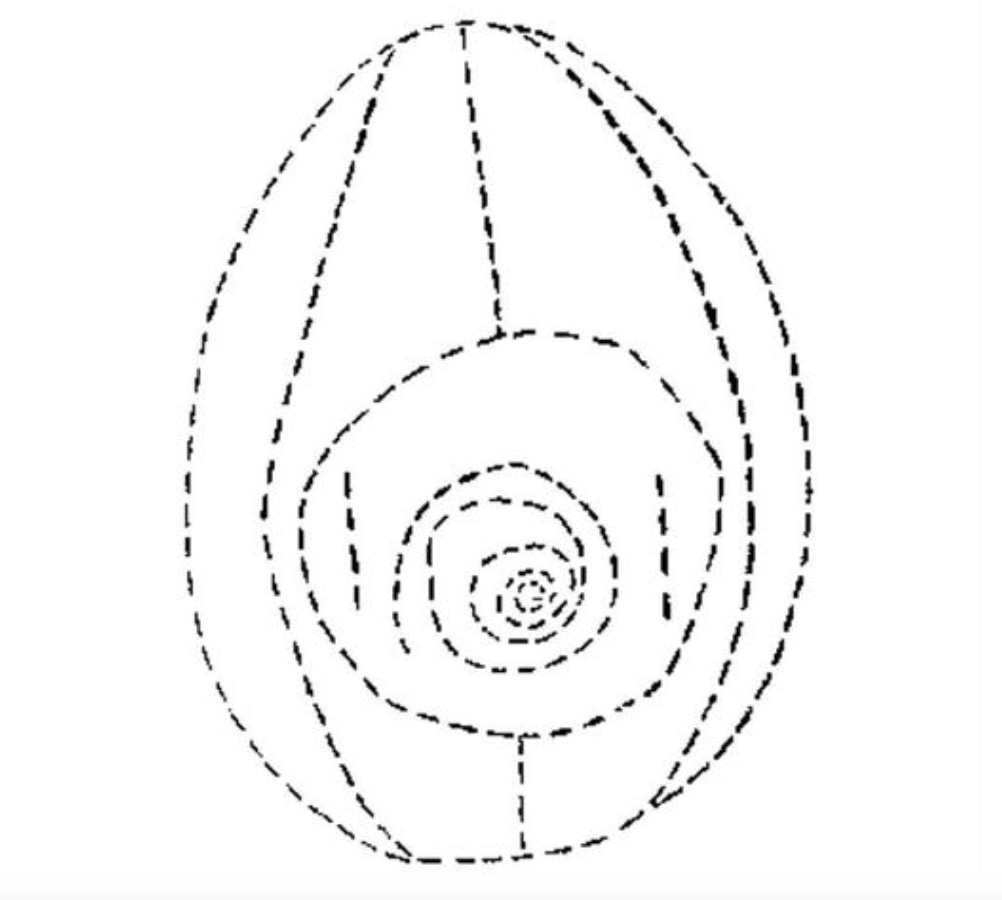

The name change has been described as a “turning point” in the company’s history—and rightly so.4 In 1986, a magazine ad announced “the rebirth of International Harvester”: “On February 20, International Harvester became Navistar International Company.” The ad features an image of an enormous egg towering over a field of smaller eggs. Above that image bold, block letters drive home the point: “WE’RE A LITTLE BIT DIFFERENT THAN MOST NEW COMPANIES.”5

“Harvester’s New Name—Chicago, January 7, 1986—The International Harvester Company, the nation’s leading producer of heavy-duty trucks, officially confirmed today that it would change its name to the Navistar International Corporation. After saying that Harvester was long considered a ‘sleepy Midwest giant,’ Donald D. Lennox, Harvester’s chairman, said he hoped the new name ‘would project a new profile for the company as a progressive, dynamic company.’ He said Navistar was a computer-generated word that he hoped would show that the Chicago-based company, which narrowly eluded bankruptcy, was ‘navigating to the stars, to a rosy future.’ International Harvester sold its name when it sold its farm equipment operations to Tenneco Inc. last year. The company’s shareholders will vote on the name change at Harvester’s annual meeting Feb. 20. If approved, the new name becomes effective the next day. The company plans to change its ticker symbol on the New York Stock Exchange to NAV from HR.”6

While “navigating the stars to a rosy future,” what became of the three key factors that observers identified with the company’s heritage and credited with both its success and longevity?

By the early 80s, the company’s agricultural equipment operations became such a financial drain on the company that it could imagine a future without it.

And when it came to restructuring for self-renewal, the company did not look to the McCormick family as a way forward. The company did not, for example, even consider renaming itself “McCormick International, Inc.” Indeed, by the mid-1980s “the influence of the founders and the values that had carried the company for decades led to what [one International executive] characterized as multiple tiers of management who were paternalistic, bureaucratic, and dependent on the existing hierarchy.”7

Agricultural technologies and family, once recognized as pillars of strength or essential assets to the company, were now understood as major liabilities.

Did the third factor suffer a similar fate? Did the company eventually have to sacrifice its “strong relations of trust with customers and dealers”? Were those very relations eventually singled out as partly responsible for the company’s decline and near collapse? In fact, all of the evidence points to the contrary.

For example, when it came to choosing a new name the company recognized that “IH had done little to promote the ‘International’ truck brand” even though that brand was “important to dealers and worthy of support.” At the time, the truck division was the company’s “only significant line of business” and it was “decided that the trucking division needed a stronger relationship with dealers, and that the new company must find some way to demonstrate support without becoming equated with the division’s line of business.”

“International Truck and Engine Company” would be the principal operating company of Navistar International, Inc. In this way, the corporation managed to strengthen its relationship with its truck dealers without being equated with that line of business.

While the company could survive the loss of its agricultural equipment operations and forge ahead while leaving its founding family behind, it went out of its way to make tangible investments in relationships with its independent dealers. Core businesses come and go and founding families pass into history, but “strong relations of trust” now more than ever appear to constitute the essence the extended commercial enterprise.

Recognizing as much, it may very well be the case that International’s own fortunes are just as tied to the fate of its dealers as “the dealers’ fortunes are directly tied to the fate” of International.

As we saw earlier, the nature of these ties are such that International’s dealers were willing to make concessions and invest in International when others would not. If such ties are indeed reciprocal, then there should be evidence of International making concessions and investing in dealers when others would not. Reversing the terms of the New York Times article cited in a previous section, we need to ask: Is there evidence of a dealer assistance or development plan, one that International “might not be crazy about but would be crazier not to have,” a plan that it would not view as concessions but as an investment in its own future?

In fact, International established and made extensive use of what it calls “Dealcor,” a program that received practically no mention in industry or academic publications. We had to search the endnotes of certain Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings made by International to find a description of this clandestine program: “Dealcor Subsidiaries” means any subsidiaries “owned” or “acquired” by Navistar International Company or one of its subsidiaries “whose principal business is a dealership of International”. Another SEC endnote explains:

“‘Dealcor Subsidiaries’ means Cedar River International Trucks, Inc.; City International Trucks, Inc.; Rocky Mountain International Trucks, Inc.; J. Price International Truck, Inc.; KCR International Trucks, Inc.; Freedom International Trucks, Inc. of New Jersey; Garden State International Trucks, Inc.; Prairie International Trucks, Inc.; and Co-Van International Trucks, Ltd; and their respective Subsidiaries, and any Subsidiaries acquired by the Company…whose principal business is a dealership…”

Such statements attest to the fact that at any given time, International has “majority-ownership” in a number of its dealerships.

Do International’s Dealcor subsidiaries mark the company’s re-entry into the retail side of the business? Are these “branch offices” or “company stores”?

A closer look at the businesses listed in the company’s 2004 SEC filing suggests otherwise: Cedar River International Trucks, Inc. would become part of Hawkeye International Trucks, Inc.8 City International Trucks, Inc. would become part of Chicago International Trucks, Inc.9 Rocky Mountain International Trucks, Inc. had already been operating under the name McCandless International Trucks, Inc. since 2001.10 A press release made by International reports that former grocery business executive Stephen Neal paid cash for J. Price International Trucks, Inc. and subsequently renamed it K. Neal International.11 KCR International Trucks, Inc. is part of a network of fifteen dealerships spread across four states which is owned and operated by Diamond Companies, Inc.12 Freedom International Trucks, Inc. continues to operate under the same name.13 Garden State International Trucks, Inc. became part of Bayshore International, Inc.14 Prairie International Trucks, Inc. merged with Archway International, Inc.15 Co-Van International Trucks, Ltd is a Canadian dealer operation with eight locations.16

If Dealcor subsidiaries do not represent International’s reentry into the retail side of the business, then what do they represent?

The SEC filings are evidence that Dealcor or some such program continues to play a role in International’s relations with its dealer network and that it had relied on such programs for decades. Recalling the magazine ad depicting International as a really big egg in a field of little eggs, it might be said that the company’s Dealcor program works something like an incubator—only instead of hatching chickens, it hatches trusted relations in the form of independent others. Not employees, but friends.

Additional evidence attests to the company’s on-going investment in its independent dealer network: when the circumstances are such that dealerships do not grow and prosper on their own, International uses Dealcor to grow a new generation of owner-managers or “dealer principals”. In terms of K’s experience learning the family business, when there is no Uncle John—a benevolent “caretaker” who is willing and able to risk more for the sake of those he is partial to—it is necessary to create one.

In this major section, we have reviewed International’s rise, fall and overhaul with an eye on what other observers have identified as key factors in the company’s heritage. In doing so, we came to focus on three such factors: the company’s roots in agricultural equipment, its founding family and its trusted relations with independent others. Of these three, only the third survived the company’s efforts to renew itself in the 80s.

Even so, other observers have overlooked or simply taken this development for granted. That fact indicates the extent to which a mature OEM like International realizes that “the new rules of the global economy” require it to be more than a “streamlined, world class manufacturer”.17

On the one hand, International’s experience attests to the fact that the more successful such a manufacturing concern becomes, the more it tends to function like a “hub” or center of gravity: the sheer inertia of the growing enterprise tends to suck the lives revolving around it in and down (e.g.,“I don’t know anything but Harvester”).

On the other hand, the OEM-dealer relationship may be the key to understanding how another, counter-tendency is at work in the logic of commercial practice—a line of escape or flight that concerns a certain “distribution of intensive principles…a worldwide intensity map”.18

By continuing to focus on that very relationship and the tendency it implies, we intend to show how the other factors continue to play important, although very different roles in that very logic.

Borucki and Barnett, p.38.

Ibid.

Concerning the overhaul of International, see in particular Klein and Greyser (1988) and Borucki and Barnett (1990).

Borucki and Barnett, p.44.

Klein and Greyser, p.24.

New York Times, January 8, 1986.

Klein and Greyser, p.3.

http://www.hawkeyetrucks.com/

http://www.chicagointernationaltrucks.com/

https://www.mccandlessintltrucks.com—“McCandless International Trucks of Colorado had been in the same location since 1954. We originally sold trucks and farm equipment under the name International Harvester Company. In 1982 we became Rocky Mountain International Trucks and dedicated ourselves solely to our customers truck and transportation needs. Rocky Mountain International Trucks officially became McCandless International Trucks in late 2001. In August 2002 we moved to our new location in Aurora. We are proud of our heritage and look forward to many more years of serving the front range of Colorado from our three locations in Aurora, Colorado Springs, and Pueblo.”

http://www.knealinternational.com/

http://www.diamondtrk.com/

http://www.freedomtrucks.com/

“Bayshore International is expanding to the South Bay, adding three new locations to better serve your needs. Wherever you find yourself in the greater Bay Area, we’re nearby and ready to serve you!” http://www.bayshoreinternational.com/

http://www.prairieinternational.com/

http://www.covanint.ca/

Borucki and Barnett, p.36.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p.165.