3.32 Records

Chapter 3: Accounting, the Controller

The next matter to consider according to the purpose statement for the dealership’s Secretary-Treasurer is “maintaining accurate and complete financial and operating records”. Maintenance, accuracy, completeness, financial, operations, records. All of these terms are “machinic indices”—exemplary indices: “we must seek to discover how the machinic indices are grouped on each of these lands that permit going beyond them”.1

“Records” must be distinguished from “reports”. The latter are based on the former. Thus far, we have only considered one kind of report, namely the “budget reports” that K helped develop during his first couple of weeks in the dealership. If reports presuppose records, then records in turn presuppose the flow of financial transactions that we described in the previous section along with another kind of flow—operational flows. Hence, there are different kinds of records, including “financial records” and “operating records”. Financial records include “accounting records” like “bank statements,” “accounts receivable” and “accounts payable”. Operating records include the company’s “inventory records,” “customer credit records,” “policies and procedures,” and “personnel files”.

The company’s records are maintained, which aims to be “accurate and complete”. Accuracy requires the establishment of procedures for cross-checking and validating results. Completeness requires the establishment of not only procedures for capturing all instances of a predetermined object but also definite periods of operation.

A running history of the dealership’s revenue-producing activities is recorded in the series of records we introduced above, namely “invoices,” “repair orders,” and “contracts”. We will take a closer look at the first of these as a case in point.

The dealership’s sales brochure (§1.21 The Brochure) informs us that the Part’s department has “$1 million in parts inventory for all makes of trucks and trailers.” We should not take for granted the fact that the brochure does not tell us how many different kinds of parts or the total number of parts that the dealership keeps on hand but instead tells us their value in dollars. At bottom, accounting concerns “a double-entry account book” that regulates the confluence of “parts,” “repair operations” and “deals” with the flow of money.

The dealership’s Parts department functions as the local warehouse and retail distributor for International’s parts business. The after-market parts business is one of International’s major business units, on par with its truck, bus and financial services units. The dealership works in close concert with International’s network of regional “Parts Distribution Centers” or “PDCs”. At the time, International furnished the dealership with “computer tapes” used to make periodic “price increases” on its business system. When the Parts department makes a purchase from its regional PDC, that transaction appears on a “dealer statement”. The dealer statement is a comprehensive accounting record for all of the transactions between a given dealership and International.

I-10 International has three Parts departments—one at the main dealership, one at Diamond Truck Center and another at the dealership in Tucson—but receives only one dealer statement. International has both required and recommended stocking levels for each and every part. Beyond this, the Parts manager must use his understanding of the local market in order to ensure that his department has the right parts at the right time in the right quantity with the aim of balancing customer expectations and needs with operating objectives defined in terms of gross margin, shipping costs and turnover.

By the time a customer requests a given part, that part has already been subject to a number of recording processes. When the part is manufactured it is assigned a unique “part number” that is recorded in any number of “parts catalogs”. When parts are shipped from a PDC to the dealership, it is accompanied by a “packing list” and followed by an “invoice”. The details of the latter eventually appear as a line item on the dealer statement. In this way, the flow of physical parts is doubled by a paper or electronic trail that captures inventory, transport and accounting information.

When a customer with an established account purchases a part, a financial record called an “invoice” is completed. Accounting supplies the Parts department with boxes of pre-printed invoices that are all sequentially numbered. Assuming the dealership’s business system computer is up and running, the invoice is automatically generated at the time of the transaction. If the system goes down, which happens from time to time, then the invoice must be generated by hand.

When this occurs a given transaction will require two distinct invoices: one hand-written invoice and another that is cross-referenced to the first when the computer system is back up again. Similarly, if the part is subsequently returned, then another, separate “credit invoice” is generated and cross-referenced to the original invoice.

Cash transactions do not require the inclusion of a customer’s information on an invoice. Because we have assumed that we are dealing with an account customer, in all likelihood the part in question was charged to that customer’s “open account”. If so, the invoice will not only include information on the part such as a brief description, quantity and price but also customer information that might include a customer “purchase order number”. The latter number indexes the recording process as it concerns the customer’s business.

An invoice, then, would be “accurate” if it includes the correct information concerning the particular transaction in question. For example, if customer X purchased the part but the invoice indicates that it was charged to customer Y, then the record is inaccurate; if part A was purchased but the invoice indicates that it was part B, then the record is inaccurate in another way.

Similarly, the recording of a transaction would be “complete” if a given invoice included all of the necessary information and all of the various kinds of possible invoices (hand-made, computer-generated and return) are accounted for and cross-referenced. For example, if the part was purchased on open account but the customer’s information is not recorded, then the invoice would be incomplete; if a return invoice does not reference the original sales invoice, then that invoice would also be incomplete.

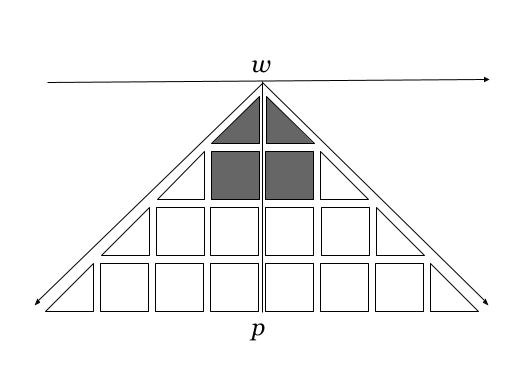

In treating such details, our attention is draw to the fact that the notion of completeness enjoys a certain relation to time. Like the dealership as a whole, the Parts department operates according to a “fiscal calendar” consisting of twelve months that begins November 1 and ends October 31. Every month the dealership’s “books” are “opened” and “closed”. All of the invoices generated in a given month constitute a set that are then determined to be complete or incomplete. For example, if the first invoice generated on October 1 is number 501 and the last invoice generated on October 31 is number 2001, then the records are complete if there are fifteen hundred invoices accounted for; if there is a gap that has not been accounted for, then the records are incomplete.

In this way, accuracy and completeness constitute the two criteria of truthfulness as it relates to the maintenance of records. The terms complement each other: the notion of accuracy is synchronic (outside of time) and that of completeness diachronic (in time). Together, they constitute a measure of truthfulness as far as records are concerned.

What is less obvious is that accuracy looks back to “company funds” while completeness looks forward to “assets”. We will come to see that such details are as important as they are subtle. Why? Because the “temporal, spatial and social ordering” that underlies and organizes the dealership’s learning curriculum is ultimately revealed through them:

“The little routines people enact, again and again, in working, eating, sleeping, and relaxing, as well as the little scenarios of etiquette they play out again and again in social interaction. All of these routines and scenarios are predicated upon, and embody within themselves, the fundamental notions of temporal, spatial, and social ordering that underlie and organize the system as a whole. In enacting these routines, actors not only continue to be shaped by the underlying organizational principles involved, but continually re-endorse those principles in the world of public observation and discourse.”2

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus, p.318.

Ortner, Sherry (1984) “Theory in Anthropology since the Sixties.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 26 (1): 126–65.