5.4 Form of the Master

Chapter 5: Service, the Controllable

Our point of department: “Learning is a process that takes place in a participation framework, not in an individual mind.”1 Moreover, the place for learning that we are mapping is not a place apart. Ours is a society in which “factories” exist apart from “schools” and processes of “socialization” exist along side “formal education systems”:

“Societies with relatively high degrees of complexity cannot seem to avoid going beyond mere socialization and mere ad hoc education. Only thus can they reproduce knowledge and capabilities acquired in long sequences of coordinated individual steps. Only this enables processes of specialization and the distribution of roles on the basis of specialization. It is quite familiar, and equally familiar is a critique of the artificiality of schools and the uselessness of what is learned there. The critique is directed primarily at curricular choices, political intervention, the cultural bureaucracy, and, more recently, the capitalism at work. It should begin with something more fundamental…”2

Having come this far, it was perhaps inevitable that we would encounter something more fundamental than the centripetal forces that guide learning conceived as “legitimate peripheral participation” and the transformation of “apprentices” into “masters”. The “challenge” of Situated Learning was always understood as “surely deeper”:

“This means, among other things, that [learning] is mediated by the differences of perspective among the co-participants. It is the community, or at least those participating in the learning context, who ‘learn’ under this definition. Learning is, as it were, distributed among co-participants, not a one-person act. While the apprentice may be the one transformed most dramatically by increased participation in a productive process, it is the wider process that is the crucial locus and precondition for this transformation. How do the masters of apprentices themselves change through acting as co-learners and, therefore, how does the skill being mastered change in the process? The larger community of practitioners reproduces itself through the formation o f apprentices, yet it would presumably be transformed as well. Legitimate peripheral participation does not explain these changes, but it has the virtue of making them all but inevitable. Even in cases where a fixed doctrine is transmitted, the ability of a community to reproduce itself through the training process derives not from the doctrine, but from the maintenance of certain modes of co-participation in which it is embedded.”3

Legitimate peripheral participation accounts for a community’s ability to reproduce itself—it draws attention to the structures and processes that are responsible for the production of both products and producers, e.g. “trousers” and “master tailors”:

“The organization of the process of apprenticeship is not confined to the level of whole garments. The very earliest steps in the process involve learning to sew by hand, to sew with the treadle sewing machine, and to press clothes. Subtract these from the corpus of tailoring knowledge and for each garment the apprentice must learn how to cut it out and how to sew it. Learning processes do not merely reproduce the sequence of production processes. In fact, production steps are reversed, as apprentices begin by learning the finishing stages of producing a garment, go on to learn to sew it, and only later learn to cut it out. This pattern regularly subdivides [the learning of] each new type of garment.”4

The profundity of this insight is perhaps matched only by its superficiality. This may explain why some readers found the claims of situated learning “overstated” and its educational implications “misguided”.5

The fundamental insight achieved by situated learning is often taken to be and used as a critique of schooling and instruction. We are not concerned with critique.

Indeed, for us the significance of situated learning is that it redirects our attention from the transformative possibilities and promises of the educational system and its cultural bureaucracy back onto to “language, architecture, bureaucracy and lines of escape” of the capitalist enterprise itself.6 By following K this far, we have reached a point that we have no choice but to follow Kafka, too: “Kafka is the great theorist of bureaucracy”. We have no choice: our problem has morphed into his problem.

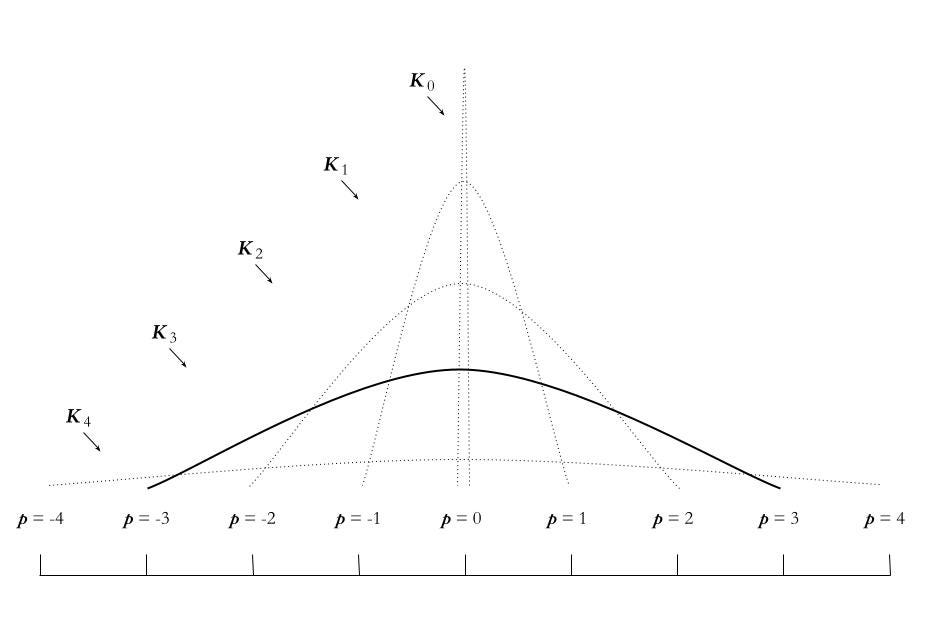

Immediate consequence: beyond “identities of mastery,” outside the concentric circles of “skill and specialization,” a social theory of learning must account for the transformation of the community itself. The form of the master is a limit form for situated learning. When it reaches that form, which it had determined to be the goal or telos of a centripetal process leading from the periphery to the center of a community of skilled producers, it starts to encounter contradictions and paradoxes:

“There may seem to be a contradiction between efforts to ‘decenter’ the definition of the person and efforts to arrive at a rich notion of agency in terms of ‘whole persons’. We think that the two tendencies are not only compatible but that they imply one another, if one adopts as we have a relational view of the person and of learning: It is by the theoretical process of decentering in relational terms that one can construct a robust notion of ‘whole person’ which does justice to the multiple relations through which persons define themselves in practice.”7

Are whole persons produced through a “centripetal development” or a centrifugal process, a centering or decentering practice?8 Like Alice, we have reached a point in our own adventure where we must ask: “Which way, which way?”9

William F. Hanks, Introduction, Situation Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, p.15.

Niklas Luhmann, Social Systems, p.207.

William F. Hanks, Introduction, Situation Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, pp.15-16.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situation Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, pp.71-72.

Anderson, J. R., Reder, L. M., & Simon, H. A. (1996). “Situated Learning and Education,” Educational Researcher, 25(4), 5-11.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, p.71.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situation Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, pp.52-53.

Ibid, p.57.

Gilles Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, p.3 and p.77.