1.321 Working Relations

Chapter 1: The Soul of Business

In a widely-read account of labor and learning the British cultural theorist observes, “the way in which manual labor is applied to production can range in different societies from the coercion of machine guns, bullets and trucks to the mass ideological conviction of the voluntary industrial army. Our own liberal democratic society is somewhere in between.”1

The French sociologist makes a similar observation. The various ways in which labor is applied to production now appear on a spectrum of experience:

“The experience of labor lies between two extremes, forced labor, which is determined only by external constraint, and scholastic labor, the limiting case which is the quasi-ludic activity of the artist-writer. The further someone moves from the former, the less they work directly for money and the more the ‘interest’ of work, the inherent gratification of the fact of working the work, increases — as does the interest linked with the symbolic profits associated with the name of the occupation or the occupation status and the quality of the working relations which often go hand in hand with the intrinsic interest of labor. (It is because work in itself provides a profit that the loss of employment entails a symbolic mutilation which can be attributed as much to the loss of the raison d’être associated with work and the world of work as to the loss of the wage.)”2

For our present purposes, the importance of these observations of contemporary industrial society is that they lend themselves to a certain visual accounting. Strictly speaking, labor is activity that “can be directed towards an exclusively economic goal, the one that money, hence forward the measure of all things, starkly designates.” This “discovery of labor presupposes the constitution of the common ground of production, that is, the disenchanting of a natural world reduced to its economic dimension alone.”3

Before we can say anything certain about what it means to learn to labor—that is, before we can say with the cultural theorist “how working class kids get working class jobs” or say for ourselves how K learned the family business—we would do well to concentrate our efforts on visualizing this common ground or economic dimension.

What is the constitution of this ground or dimension? Moreover, how exactly is social existence differentiated as a function of it? A directed arrow affords us an initial visualization and provisional answer.

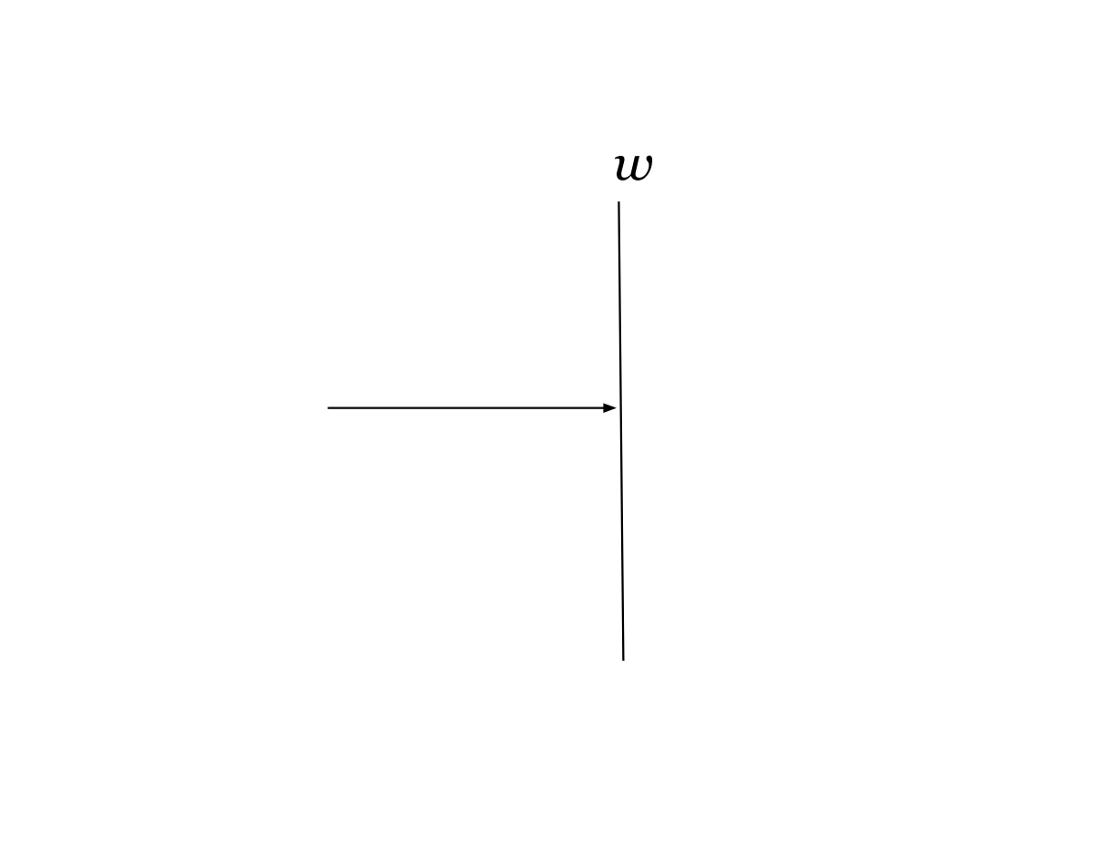

Whether we are concerned with the assembly line and the factory worker or lines of poetry and the artist-writer, labor or productive activity can be reduced to three terms and take the form of a directed graph or vector: “A vector may be represented graphically by an arrow. The magnitude of the vector corresponds to the length of the arrow, and the direction of the vector corresponds to the angle between the arrow and a coordinate axis. The sense of the direction is indicated by the arrowhead.”4 Armed with this dictionary definition of a vector, we can depict the situation of wage-labor in general (see Figure 1.19 below).

We can then imagine the two limiting cases—“forced labor” and “scholastic labor”—as vectors that are identical in terms of direction and sense yet vary in magnitude.5 The former can be conceived as drawing near the minimum and the latter as drawing near the maximum in the total possible range in magnitude of any particular labor vector. Looking at Figure 1.19, we will say that those who “work directly for money” tend toward the minimum limit—that is, toward the shortest possible magnitude; and those who work for other reasons, for example “the ‘interest’ of work, the inherent gratification of the fact of performing work,” tend toward the maximum limit—that is, toward the longest possible magnitude.

This is only half of the story. The “twofold truth of labor” cannot be understood apart from considerations of “employer’s strategies,” of profit-taking, capital and the agents of capital.

Recognizing this, we will use the phrase “working relations” to designate a social aggregate that accounts for the conjunction of labor and capital, relations of production and property relations, the specific combination of revenue-producing activity systems and the mechanisms of control and monopoly appropriation of profits.

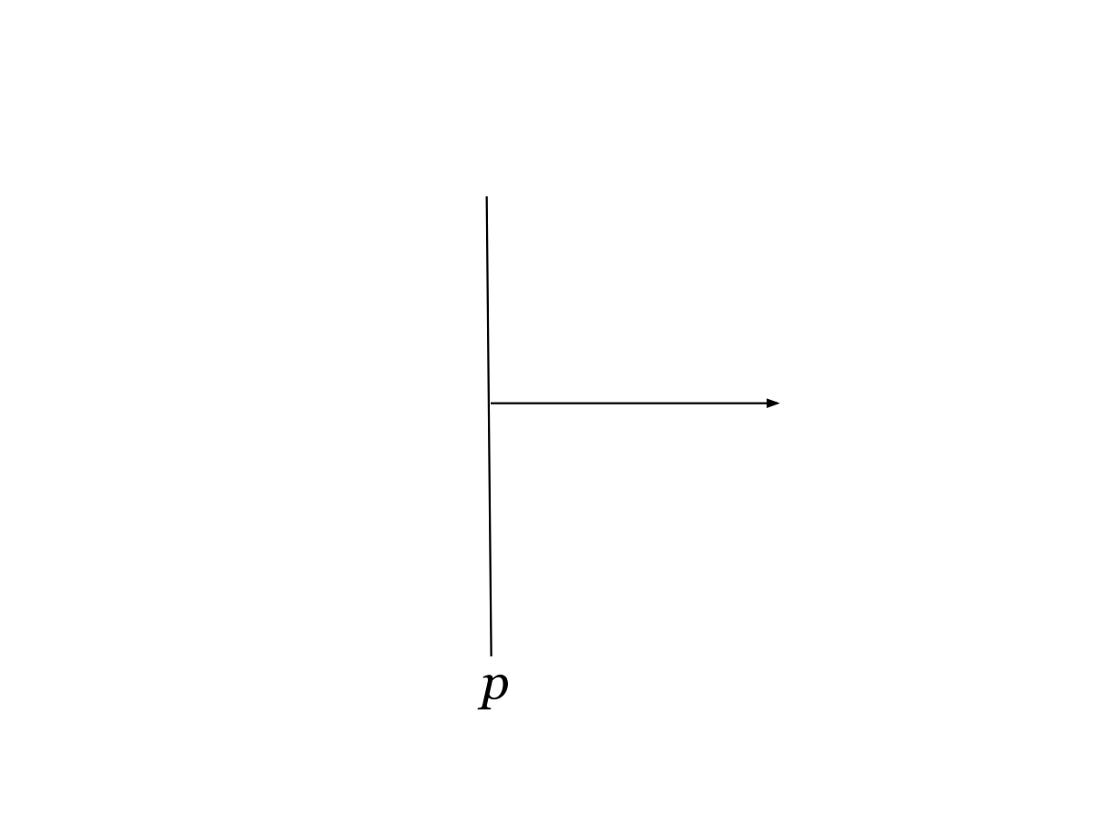

Both sides of society’s working relations can be represented as vectors, with capital or property relations appearing as a vector the sense of which is determined to move away from money-profit (p in Figure 1.20).

The French sociologist’s characterization of the margin of freedom that can be used to distinguish particular forms of labor is analogous to a problem concerning capital when he speaks of different “forms of capital”: “economic,” “social,” “cultural,” as well as “the symbolic effects of capital”.6 We can then speak of an ambiguity of capital that may take into account the difference between the capitalist, on the one hand, and the agents of capital, on the other.

Assuming as much, we will say that the ambiguity of labor and that of capital differ in kind and this difference can be visualized. On the one hand, as labor moves unambiguously toward money-wage (the moment when wealth buys labor as labor’s destination or aggregate of arrival), its indeterminacy resides in its origo or aggregate of departure, represented by variations in the magnitude of the labor vector. On the other hand, the ambiguity of capital is precisely the opposite, as now it is the origo or point of departure that is unambiguous and the ultimate destination, telos or aggregate of arrival that is indeterminate.7

The margin of freedom left to the worker, the same margin that the sociologist associates with an “increase in [a worker’s] well-being,” produces or is accompanied by a kind of blindness: those who enjoy a certain health determined by “the real conditions of the performance of [their] labor” are those who fall prey to a “misrecognition” or “miscognition of the objective truth of labor as exploitation”.8 In this way, we can speak of the “well-being” of the worker without sounding utopian or witlessly contributing to society’s innumerable forms of “symbolic violence”.9

This is why it is important to deal with the matter at the level of society’s working relations: without denying the fact that the more labor invests in work the less it recognizes the conditions of exploitation, when such an investment reaches its maximum level—the point at which labor becomes a “quasi-ludic activity”—misrecognition of the conditions of exploitation gives way to a recognition of an entirely different order. The question then becomes what does the “blindness” or miscognition of quasi-ludic activity allow us to see?10

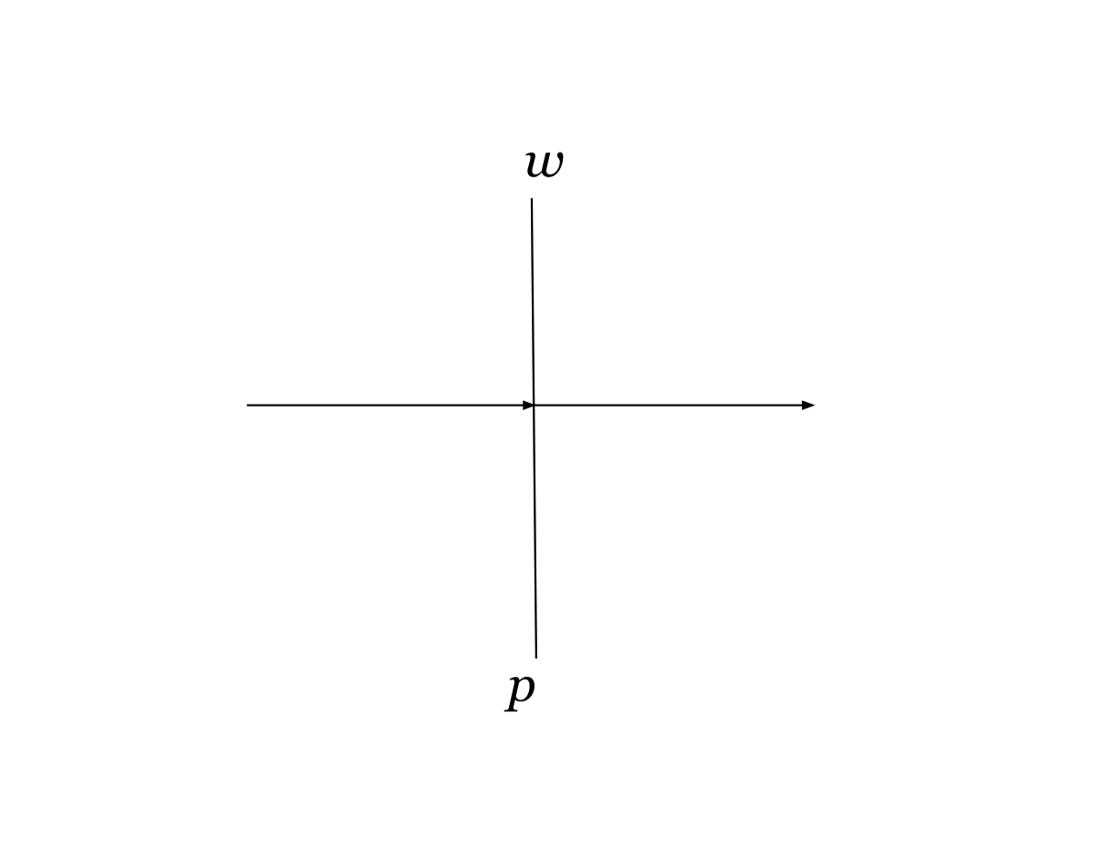

By superimposing the previous two figures we afford ourselves a possible answer (see Figure 1.21 below).

The resulting figure depicts the dealership’s working relations as essentially determined by a certain conjunction of labor and capital: labor effectively runs into money-wages (w) and capital runs away with money-profit (p).

Are the two sides of society’s working relations related in other, perhaps, profound ways? Do their respective forms of indeterminacy correspond or co-vary in any systematic or predictable way?

In fact, these questions lend themselves to empirical investigation, with the simplest possible case involving a labor vector tending toward the minimum limit and corresponding to Marx’s “wage labor”.11 According to the sociologist, it is precisely in such a case that labor clearly recognizes the conditions of exploitation that define the capitalist mode of production: in effect, those who labor directly for money-wages stare capital in the face.

Having stated the problem in these terms, empirical observation suggests that the sociologist’s “objective truth” is a function of bilateral symmetry—that is, a one-to-one mapping of labor onto capital as a function of society’s working relations, with wage labor on the left and the mechanism of monopoly appropriation of profits or private property on the right.

In the following subsection, we will see that the correlation or co-variation between labor and capital continues, especially at magnitudes that tend toward the maximum extension of society’s working relations.

Paul Willis, Learning to Labor: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Job, p.1.

Pierre Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditations (Stanford University Press, 2000), pp.202–3.

Pierre Bourdieu, The Logic of Practice, p.117. Bourdieu adds, the “discovery of labor presupposes the constitution of the common ground of production, that is, the disenchanting of a natural world reduced to its economic dimension alone.”

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Statics/Forces_As_Vectors#Graphically.

At this point in our demonstration, we are merely relying on a dictionary definition of the term “vector” which “requires for its complete specification a magnitude, direction and sense and that is commonly represented by a line segment the length of which designates the MAGNITUDE of the vector, the orientation of which designates the DIRECTION of the vector, and the SENSE of which is designated by an arrowhead at one end of the segment” (Webster’s Third New International Dictionary). We are taking baby-steps on the road to thinking “diagrammatically,” cf. Gilles Châtelet, Figuring Space: Philosophy, Mathematics, and Physics (Springer, 1999); Rocco Gangle, Diagrammatic Immanence: Category Theory and Philosophy (Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

Pierre Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditations, p.242. See also P. Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” in John G. Richardson, ed. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (Greenwood Press, 1986), pp.241–58.

We could have said, but will refrain until we must: on the one hand, “relatively deterritorialized” labor is “reterritorialized” on the body of capital-money; and, on the other, the capitalist is deterritorialized absolutely, but negatively. We will reach a point in our story where it will be “necessary to distinguish between three types of deterritorialization: the first type is relative, proper to the strata, and culminates in signifiance; the second is absolute, but still negative and stratic, and appears in subjectification (Ratio et Passio); finally, there is the possibility of a positive absolute deterritorialization on the plane of consistency or the body without organs,” Gilles and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p.134. All of this being a function of “perceptual semiotics,” Ibid, p.23.

Pierre Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditation, p.202.

Ibid, pp.164–205.

See Rocco Gangle’s chapter “Deleuze and Expressive Immanence,” and the section “Thinking From Blindness” in particular, in his Diagrammatic Immanence. On the road to “great health,” we must confront blindness, nonsense and stupidity.

Pierre Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditations, p.202n29.