1.322 The Learning Curriculum

Chapter 1: The Soul of Business

In the previous section, we set out from the field’s working relations, isolating and attempting to visualize the “relations of production and property relations which are established not between concrete individuals but between atomic bearers of labor-power or representatives of property” as a function of commercial practice.1 In doing so, we imagined relations of production mapping onto property relations by swinging around the pole or vertical axis of money-capital.

It is precisely at this point that the study of learning asserts its importance as it may be impossible to discern the “objective causal structure”2 and profound systematicity that define the field of commercial practice without assuming the perspective of the newcomer-apprentice whose trajectory of participation may extend from one end of that structure or field to the other.

“One of the most dangerous ideas for a philosopher is, oddly enough, that we think with our heads or in our heads. The idea of thinking as a process in the head, in a completely enclosed space, gives him something occult.”3

For us, learning, cognition and—in the final instance—thought, are not to be found “in our heads” but precisely in the trajectories and movements that define the field of participation. This is why it is imperative that we follow the philosopher-director and “look only at the movements.”

For the social problem as we have come to understand it is not simply “a movement which would directly touch the soul,” but a movement “which would be that of the soul.”4

We have recognized for centuries that “thought” is “not always encapsulated within the brain, that it could be everywhere...outside...in the morning dew.”5 By concerning themselves with “cognition in the wild,” cognitive ethnographers have rediscovered and unwittingly continued a 19th-century project of the philosophy of nature and Romantic idealism.6

“We know that one of the major ambitions of the philosophy of nature was the patient explanation of the Absolute. It is no longer a question of letting oneself be subjugated by the Absolute (whether in relegating it to the ineffable, or setting it down formally), but of distinguishing stops, problematic hinges where nature and the understanding cross one another, where the first turns itself into ‘visible Understanding and the second invisible Nature,’ where an articulation between the individuation of Being to be known and that of the knowing subject becomes apparent.”7

The critical contribution made by cognitive ethnography to this project is the notion of legitimate peripherality: “Legitimate peripherality is a complex notion, implicated in social structures involving relations of power. As a place in which one moves toward more-intensive participation, peripherality is an empowering position.”8

In Part II of our report, we document the singular moments of K’s passage from the field’s minimum limit to its maximum limit, from a state that “scarcely rate[s] a score for being alive” to a state of relative “well-being”.9

In doing so, we open ourselves to the possibility of locating not only a clear case of learning conceived as “legitimate peripheral participation,” but more profoundly of determining a series of forms that unfolds in step-wise fashion and that also deserves to be called learning.10 From this perspective, our own contribution appears to touch on or approach something like “the learning of learning”.11

As we will see in the course of this lengthy section, it is imperative that our patient laying out of the field “bring ‘degrees of development or perfection’ into the picture.”12 The construction necessarily proceeds in order along three dimensions: horizontal, vertical and diagonal. Later on and elsewhere, we will see that the field of participation thus revealed is a profound instance of an "electrogeometric space".13

Legitimate Peripheral Participation. The anthropology of apprenticeship has established, under widely varying historical periods and cultural contexts, a kind of progression in which the learner moves “backward” relative to the corresponding “production process”.14

Our initial task is to specify the indexical ground or point of departure and the terminus or point of arrival of the learner-newcomer. What appear as the points of departure and arrival for the learner-newcomer should appear as precisely the opposite for full participants in the productive process: “the ordering of learning and everyday practice do not coincide: production activity-segments must be learned in different sequences than those in which a production process commonly unfolds, if peripheral, less intense, less complex, less vital tasks are learned before central aspects of practice.”15

The canonical example of legitimate peripheral participation is the practice of tailoring: “tailors’ apprentices…progressively move backward through the production process to cutting jobs”.16

We cannot allow the simplicity of this insight to mislead us: its matter-of-factness tends to obscure its analytical power and its true importance will only be apparent when our construction nears completion.

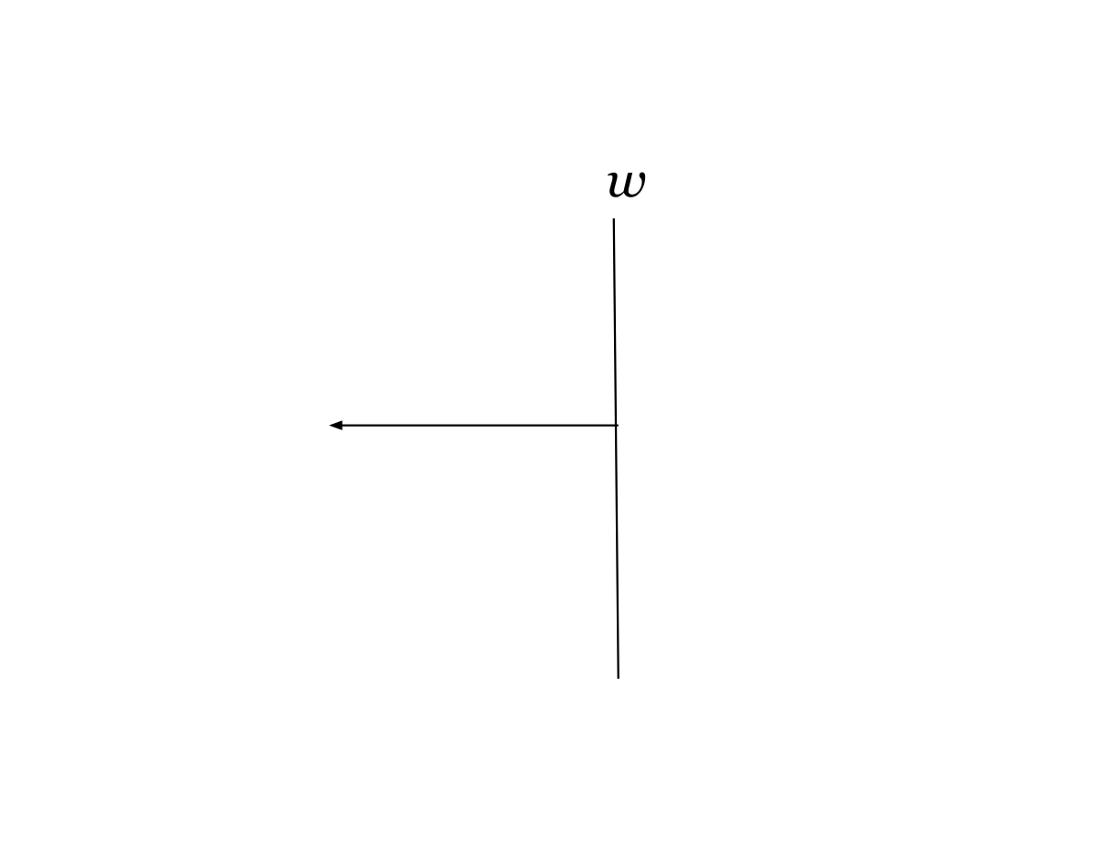

As the production process in our target situation is tied to the economy of money-wages, legitimate peripheral participation can be represented using the same directed arrow scheme that we introduced and employed in the previous section (see Figure 1.22 below).

While the magnitude of the learning vector is determined by the relations of production that define a given activity system, its sense is a function of legitimate peripheral participation.

By counting “activity-segments,” which is possible to the extent that language renders these segments discreet by labeling them, we afford ourselves the means of empirically measuring the magnitude of a given labor-learning vector.

Consider again the case of the tailor’s apprentice: “Learning processes do not merely reproduce the sequence of production processes. In fact, production steps are reversed, as apprentices begin by learning the finishing stages of producing a garment, go on to learn to sew it, and only later learn to cut it out.”17 In this account, we find three activity-segments, which we can gloss with labels.

cutting < > sewing < > finishing

The “concept of community underlying the notion of legitimate peripheral participation, and hence of ‘knowledge’ and its location in the lived-in world, is both crucial and subtle.”18

Given a single community of practice such as the case of Vai and Gola tailors, learning conceived as legitimate peripheral participation is demonstratively operative. In one sense, the community of tailors produces suits; in another, it produces tailors. As our diagram suggests, learning conceived as such concerns a network of flat or horizontal relations that unfold along with the arrow of time.

Power is measured in terms of degrees of participation: a participant who enjoys three degrees of participation is empowered more than a participant who enjoys only two degrees of participation and a participant who enjoys two degrees of participation is empowered more than a participant who enjoys only one degree of participation.

Here, power is conceived as a participant’s capacity to produce or create. And in this way, we are led to think of differentiated social existence quantitatively: an apprentice is defined by one degree of participation, a master-apprentice by two and a master by three. The peripherality of the apprentice is legitimized to the extent that one degree becomes two and two becomes three.

At this point in the construction, another question asserts itself: if participants are differentiated by degrees of participation, can we apply the same line of reasoning to diverse activity-systems? In other words, is there evidence that activities-systems themselves are differentiated by degrees of participation?

We have seen how the anthropology of apprenticeship “situated learning in the trajectories of participation in which it takes on meaning.” The basic unit of analysis is not the individual but the activity-system conceived as a “community of practice”: “community of practice is a set of relations among persons, activity and world, over time and in relation to other tangential and overlapping communities of practice.”19

Unlike the case of Vai and Gola tailors, our target situation is clearly embedded in the world of contemporary industrial society and involves not one community of practice but several. What form does apprenticeship learning take when the situation in question is an economic organization that combines a number of distinct revenue-producing activity systems such as K experienced in the dealership?

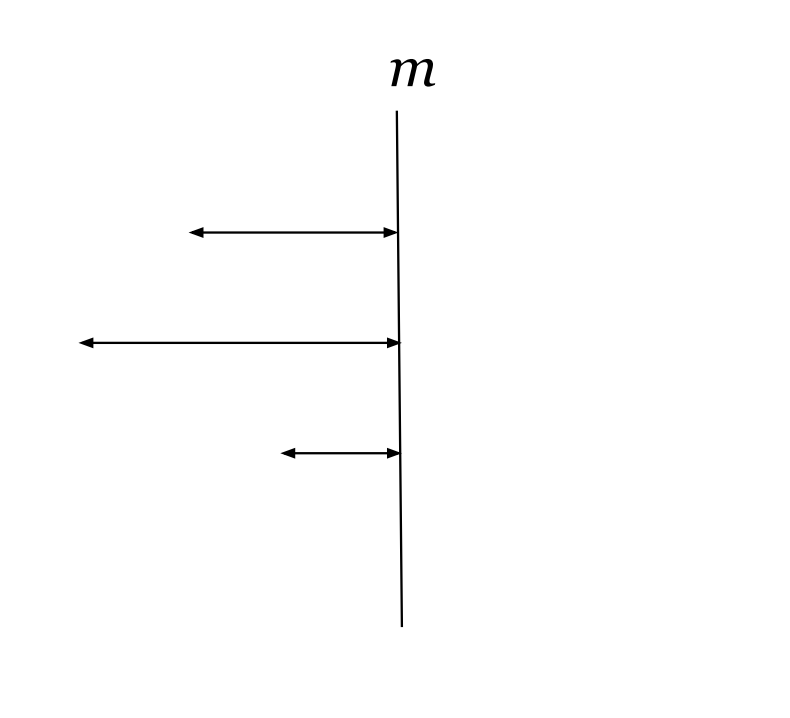

Tangential Structures. Given the terms of our question and anticipating our detailed description of K’s experience in Part II, we can imagine a situation involving three communities of practice each characterized by an activity system with a different number of activity-segments or degree of power (see Figure 1.23 below).

The dual sense or bi-directionality of the lines indicates that each of these activity-systems is a functioning community of practice, meaning that each is capable of both producing some sort of valued good or service while effectively reproducing itself: in one sense or direction (from left to right), each community is a revenue-producing, wage-earning, profit-making system; and in the other direction (from right to left), each is a producer-making system defined by legitimate peripheral participation.

What is striking about this scenario and what our diagram makes apparent is the organizing function of the tangential structure of money-capital (m). It is precisely that structure which serves as a common target or aggregate of arrival for otherwise disparate communities. Moreover, such a structure is not defined by a power or capacity to produce and subject to an analysis in terms of movement and degrees of participation. On the contrary: relative to the back and forth movements that define communities of practice, money-capital appears motionless or at rest; and relative to the degrees of participation that determine a diversity of roles and productivity that further characterize communities of practice, money-capital appears as necessarily determined to be something less than one degree or lower than the lowest. Its essence and its power appear to stem from the fact that it is stationary and a degree zero relative to the diverse activity systems that attach themselves to it. For these reasons, money-capital is necessarily represented as perpendicular to the communities of practice attached to it and that it somehow organizes; it appears as a vertical structure extending the length of the field, unlimited compared to the finite and horizontal structure of productive activity-systems.

By conceiving of learning as legitimate peripheral participation relative to a single community of practice, we remain indifferent to the fact that the larger situation or world consists of parallel communities and tangential structures. Moreover, this indifference limits those communities to producing nothing more than marketable goods and services and to reproducing members who remain subject to the organizing influence or simple tyranny of money-capital.

It is under these conditions that stentorian calls are made for “workers of the world to unite,” for the formation of unions and parties that—despite their importance—remain proxies of and peripherals to money-capital and contribute “axioms” to the “capitalist axiomatics”:

“You say you want an axiom for wage earners, for the working class and the unions? Well then, let's see what we can do—and thereafter profit will flow alongside wages, side by side, reflux and afflux. An axiom will be found even for the language of dolphins.”20

Overlapping communities. The ultimate object of a social theory of learning is nothing more or less than revolution. As a social theory of learning, legitimate peripheral participation is entirely necessary but altogether inadequate. It must be conceived as a moment in a complex process and communities of practice as parts of larger systems of social relations. Legitimate peripheral participation accounts for learning when the field of participation is determined by its working relations.

On the way to a social theory of learning that is truly adequate to our needs, we must show precisely how those working relations are arranged in such a way that legitimate peripheral participation gives way to a second and more profound moment in a more general process and how communities combined to form regions of the broader field.

Now we ask: what happens when the parallel communities of practice under consideration are no longer simply determined by a common tangential social structure? That is, what happens when legitimate peripheral participation moves away from money-capital, not only toward increasingly-intense activity segments but across and toward increasingly powerful activity systems or communities of practice?21

Our working model assumes that the complete specification of a vector entails three terms:

For magnitude, we found no reason—empirical or theoretical—to distinguish labor and learning.

For sense, ethnographic observations of apprenticeship and the concept of legitimate peripheral participation led us to see the difference between labor and learning as a simple reversal of sense. This now appears as an obvious difference, one that continues to presume a literal or tight coupling of labor and learning.

For direction, we depicted labor-learning vectors as horizontal lines or bars and tangential structures as vertical lines or columns. What we have yet to consider is the possibility of elements in the field whose direction or orientation is neither horizontal nor vertical, but diagonal.

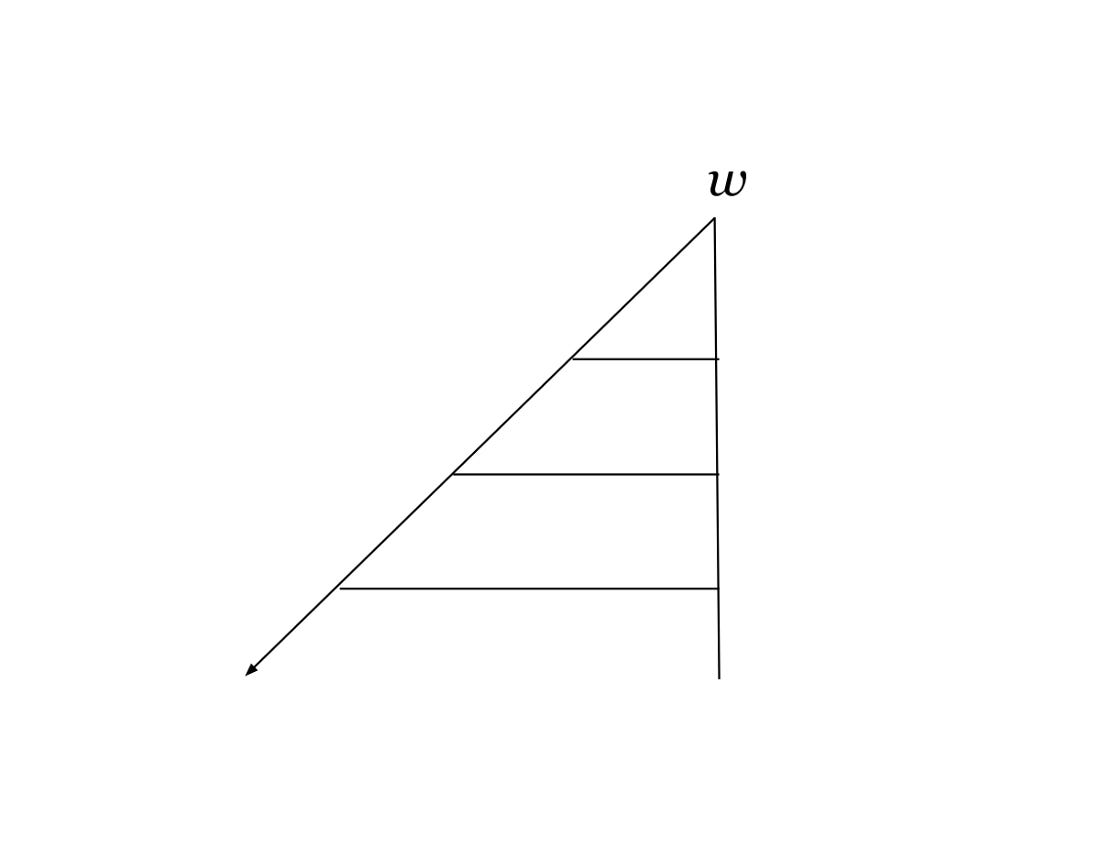

When we recognize the possibility that the direction of the learning-vector in question may be determined independently of the direction of the related labor-vectors—a determination that attests to a loose rather than a tight coupling—a second scenario presents itself (see Figure 1.24 below).22

What is immediately apparent when we compare Figure 1.24 with Figure 1.23 is the importance of taking into consideration relations between overlapping communities of practice for a social theory of learning. Why?

It now appears that the essence of situated learning—namely, “sociability”23—remains hidden or obscured not only when we restrict our observations to the individual but even when we limit ourselves to considering the activity system of a single community of practice. Indeed, only when learning sheds its feigned modesty or apparent deference to productive activity do we observe its complex relations between heterogeneous communities of practice and other social structures.

Labor and learning are practically the same in terms of magnitude, obviously distinguished by sense, and essentially heterogeneous in terms of direction or orientation. Learning is uncoupled from the labor process when we are able to determine its direction as diagonal or transversal relative to both the horizontal lines of parallel forms of productive activity and the vertical line of the economic instance.

Having come this far, we must assume that even in the case of isolated communities of practice (for example, the Gola tailor’s community or a firm or company consisting of a single department), learning always deviates from the direction of the labor-vector (see Figure 1.25 below).

The fact that the direction and sense of the learning-vector determines it to move away from rather than toward the limit case of wage-labor—that is, the zero point of intensity (w)—indicates that even the restricted case of legitimate peripheral participation concerns increasing intensity and is a truly empowering process.24

Conceived as such, our theory of learning accounts for social reproduction as well as the possibility of “anarchy” and “social upheaval (in other words, freedom, which is always hidden among the remains of an old order and the first fruits of a new).”25

When the learning process is no longer defined only in relation to overlapping communities of practice but in terms of a more general movement that takes into consideration the social field as a whole, we find that all of the characteristics of legitimate peripheral participation remain intact so long as one recognizes that the “backward” movement only relates to half of the field, namely the half defined by a community’s or communities’ productive “capacity”.

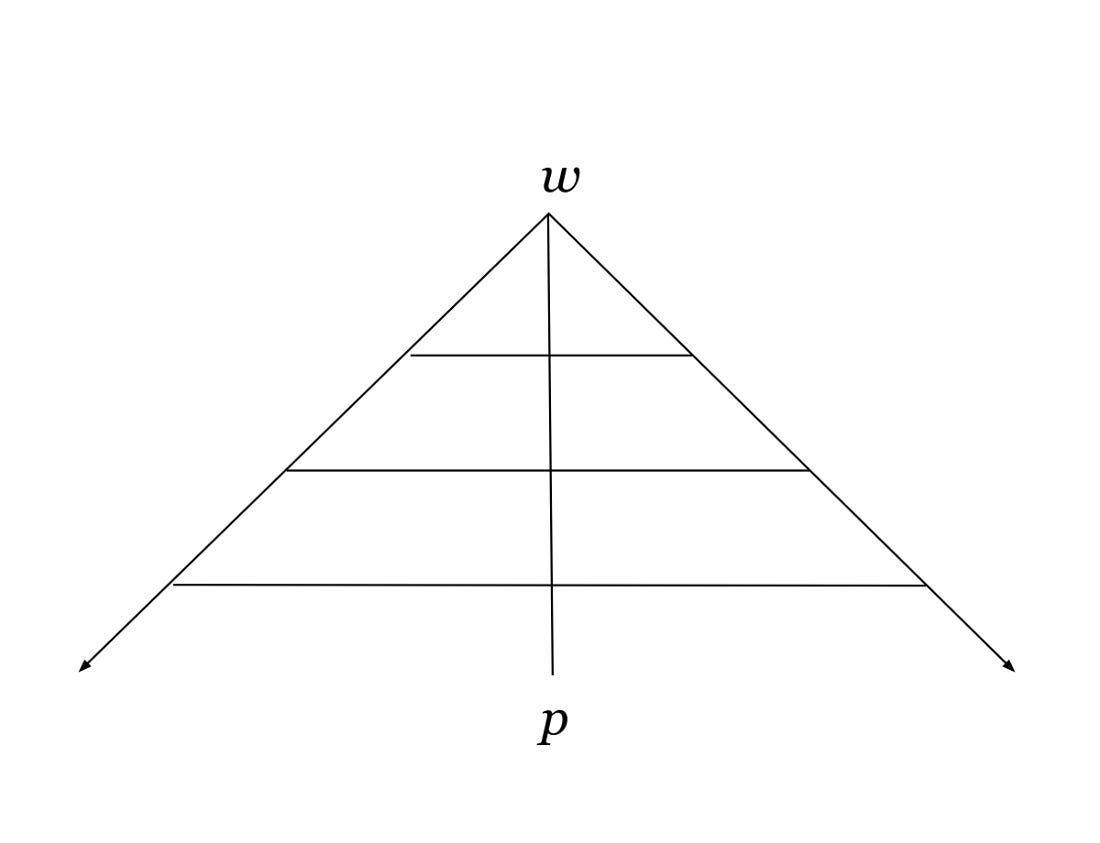

Yet, given the preliminary results above, we “must increase the possibility for movement backward and forward.”26 What then appears is a decentering movement going from the extensive to the intensive and the possibility of other movements including folding and unfolding. In this way, the outline of the learning curriculum emerges in its entirety (see Figure 1.26 below).

The center of the field is defined by the economic instance (money-capital), now determined as simultaneously a function of both wages (w) and profit (p). The field of participation itself is the ultimate ground of commercial practice, not this or that community, department or property relation. It is only the field which constitutes a “whole…whose combinations create a landscape—shape, degrees, textures—of community membership”.

Paradoxically, we must say that the center of the field is the periphery with respect to situated learning: when learning is understood as simultaneously a decentering movement relative to the “specific gravity” shaping the field of commercial practice, namely the relations of extensity that determine the role of money as a general equivalent, and a center-seeking or “centripetal movement” with the goal of something like “full participation” defined in terms of relations of intensity:

“There may seem to be a contradiction between efforts to ‘decenter’ the definition of person and efforts to arrive at a rich notion of agency in terms of ‘whole persons’. We think that the two tendencies are not only compatible but that they imply one another, if one adopts as we have a relational view of the person and of learning: it is by the theoretical process of decentering in relational terms that one can construct a robust notion of ‘whole person’ which does justice to the multiple relations through which persons define themselves in practice.”27

The important thing to stress at this point is that the field of participation promises to do more than simply depose relations of extensity (horizontal and vertical) by putting relations of intensity (diagonal or transversal) in their place.

Rather, it offers us an account of how the one is effectively transformed into the other and vice versa. We will show that the objective field in question is characterized by both sets of relations, and that such a situation has important consequences—for it is "true that at the heart of power relations and as a permanent condition of their existence there is an insubordination and a certain essential obstinacy on the part of principles of freedom" and "there is no relationship of power without the means of escape or possible flight.”28

Gilles Deleuze, Difference & Repetition, p.186.

Ibid, p.132.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Zettel (605 & 606)

Ibid, p.9.

Gilles Châtelet, Figuring Space, p.14.

Edwin Hutchins, Cognition in the Wild (MIT Press, 1996).

Gilles Châtelet, Figuring Space, p.89.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation (1991), p.36.

Paul Willis, Learning to Labor: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs (1981), p.2.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning, p.29. “Learners inevitably participate in communities of practitioners and that the mastery of knowledge and skill requires newcomers to move toward full participation in the sociocultural practices of a community.”

Gilles Châtelet, Figuring Space, p.8 and p.14.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p.46.

“Electrogeometric space is realized by the articulation of the translation-rotation duality with that of the electrical field and magnetic field. The translations superpose themselves exactly on the motions of the charges rushing down the slope of potentials and rotations that make these planes of light polarization pivot,” Gilles Châtelet, Figuring Space, p.175

Michael W. Coy, ed. Apprenticeship: From Theory to Method and Back Again (1989)

Situated Learning, p.96

Ibid, p.69-72.

Ibid, p.72.

Ibid, p.98.

Ibid, p.121.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus, pp.237-239.

“As a place in which one moves toward more-intensive participation, peripherality is an empowering position,” Ibid, p.36. If learning is indeed an “empowering” process, we can restate our question by asking: what happens when the margin of freedom of the labor-learning vector or well-being of the worker increases? In “many work situations, the margin of freedom left to the work (the degree of vagueness in the job description which gives some scope for maneuver) is a central stake,” Pierre Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditations, p.204. In relating “more-intensive participation” to “margin of freedom,” it should be apparent that we are approaching from a different angle “the real tendency towards increasing intensification of labor processes” that Paul Willis, following Harry Braverman, sees in the case of “monopoly capitalism” (Paul Willis, Learning to Labor, p.180). For example, the terms we have adopted here would determine that tendency to be one towards less-intensive forms or fewer degrees of participation and a shrinking margin of freedom. It would seem to follow, then, that legitimate peripheral participation draws attention to social formations that might depend on or exhibit an inverse or counter tendency to “the degradation of work,” Harry Braverman, Labor and Monopoly Capital: the Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, (Monthly Review Press, 1975).

“The objectification that was necessary to constitute wage labor in its objective truth has masked the fact which, as Marx himself indicates, only becomes the objective truth in certain exceptional labor situations: the investment in labor, and therefore miscognition of the objective truth of labor as exploitation, which leads people to find an intrinsic profit in labor, irreducible to simple monetary income, is part of the real conditions of the performance of labor, and of exploitation,” Pierre Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditations, p.202. See also Bourdieu’s note concerning the essential “indifference” that Marx has to assume in order to arrive at an objective understanding of “wage labor”. When learning is conceived as a diagonal or transversal vector relative to the labor process itself, Marx’s wage-labor (the significance of which, as Bourdieu is careful to point out, is more theoretical than descriptive of actual work situations) effectively appears precisely at the ideal point where the learning-vector touches the economic instance (w).

Gilles Deleuze, Difference & Repetition, p.208.

Such an analysis is indicative of the way we mean to follow Lave and Wenger when they “place more emphasis on connecting issues of sociocultural transformation with the changing relations between newcomers and old-timers in the context of a changing shared practice,” Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning, p.49.

Gilles Deleuze, Difference & Repetitions, p.143 and p.198.

Michael Foucault, “The Masked Philosopher,” in Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth (Paul Rabinow, ed. The New Press, 1998), p.326.

Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, Situated Learning, pp.53–4.

Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” in Hubert L. Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow, Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, 2nd Edition (University of Chicago Press, 1983), p.225.